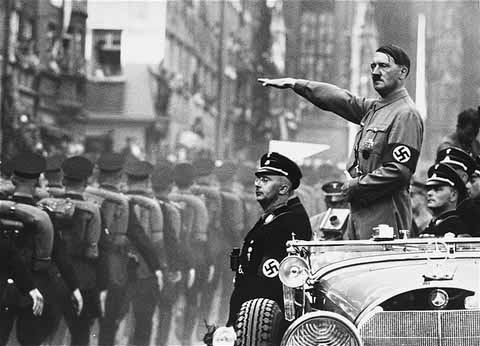

Life history of Adolf Hitler

(1889-1945)

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) was

the founder and leader of the Nazi Party and the most

influential voice in the organization, implementation and execution of

the Holocaust, the systematic extermination and ethnic cleansing of six

million European Jews and millions of other non-aryans.

Hitler was the Head of State, Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces and guiding spirit, or fuhrer, of Germany's Third Reich from 1933 to 1945.

Early Years

|

Born in Braunau am Inn, Austria,

on April 20, 1889, Hitler was the son of a fifty-two-year-old

Austrian customs official, Alois Schickelgruber Hitler, and his

third wife, a young peasant girl, Klara Poelzl, both from the

backwoods of lower Austria. The young Hitler was a resentful,

discontented child. Moody, lazy, of unstable temperament, he was

deeply hostile towards his strict, authoritarian father and strongly

attached to his indulgent, hard-working mother, whose death from cancer

in December 1908 was a shattering blow to the adolescent Hitler.

After

spending four years in the Realschule in Linz, he left

school at the age of sixteen with dreams of becoming a painter.

In October 1907, the provincial, middle-class boy left home for

Vienna, where he was to remain until 1913 leading a bohemian,

vagabond existence. Embittered at his rejection by the

Viennese Academy of Fine Arts, he was to spend "five years of

misery and woe" in Vienna as he later recalled, adopting a

view of life which changed very little in the ensuing years,

shaped as it was by a pathological hatred of Jews and

Marxists, liberalism and the cosmopolitan Habsburg monarchy.

Existing

from hand to mouth on occasional odd jobs and the hawking of sketches

in low taverns, the young Hitler compensated for the frustrations of a

lonely bachelor's life in miserable male hostels by political harangues

in cheap cafes to anyone who would listen and indulging in grandiose

dreams of a Greater Germany.

In Vienna he

acquired his first education in politics by studying the

demagogic techniques of the popular Christian-social Mayor, Karl

Lueger, and picked up the stereotyped, obsessive

anti-Semitism with its brutal, violent sexual connotations and concern

with the "purity of blood" that remained with him to the end

of his career. From crackpot racial theorists like the

defrocked monk, Lanz von Liebenfels, and the Austrian

Pan-German leader, Georg von Schoenerer, the young Hitler

learned to discern in the "Eternal Jew" the symbol and cause

of all chaos, corruption and destruction in culture, politics

and the economy. The press, prostitution, syphilis, capitalism,

Marxism, democracy and pacifism--all were so many means which "the

Jew" exploited in his conspiracy to undermine the German

nation and the purity of the creative Aryan race.

World War I

|

In May 1913 Hitler left Vienna for

Munich and, when war broke out in August 1914, he joined the Sixteenth

Bavarian Infantry Regiment, serving as a despatch runner. Hitler proved

an able, courageous soldier, receiving the Iron Cross (First Class) for

bravery, but did not rise above the rank of Lance Corporal. Twice

wounded, he was badly gassed four weeks before the end of the war and

spent three months recuperating in a hospital in Pomerania. Temporarily

blinded and driven to impotent rage by the abortive November 1918

revolution in Germany as well as the military defeat, Hitler, once

restored, was convinced that fate had chosen him to rescue a humiliated

nation from the shackles of the Versailles Treaty, from Bolsheviks and

Jews.

Assigned by the Reichswehr in the summer

of 1919 to "educational" duties which consisted largely of spying on

political parties in the overheated atmosphere of post-revolutionary

Munich, Hitler was sent to investigate a small nationalistic group of

idealists, the German Workers' Party. On 16 September 1919 he entered

the Party (which had approximately forty members), soon changed its name

to the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) and had imposed

himself as its Chairman by July 1921.

Hitler Becomes a Leader

Hitler

discovered a powerful talent for oratory as well as giving

the new Party its symbol — the swastika — and its greeting "Heil!."

His hoarse, grating voice, for all the bombastic,

humourless, histrionic content of his speeches, dominated

audiences by dint of his tone of impassioned conviction and

gift for self-dramatization. By November 1921 Hitler was recognized

as Fuhrer of a movement which had 3,000 members, and boosted his

personal power by organizing strong- arm squads to keep order

at his meetings and break up those of his opponents. Out of

these squads grew the storm troopers (SA) organized by

Captain Ernst Röhm and Hitler's black-shirted personal

bodyguard, the Schutzstaffel (SS).

Hitler

focused his propaganda against the Versailles Treaty, the "November

criminals," the Marxists and the visible, internal enemy No. 1, the

"Jew," who was responsible for all Germany's domestic problems. In the

twenty-five-point programme of the NSDAP announced on 24 February 1920,

the exclusion of the Jews from the Volk community, the myth of Aryan

race supremacy and extreme nationalism were combined with "socialistic"

ideas of profit-sharing and nationalization inspired by ideologues like

Gottfried Feder. Hitler's first written utterance on political questions

dating from this period emphasized that what he called "the

anti-Semitism of reason" must lead "to the systematic combating and

elimination of Jewish privileges. Its ultimate goal must implacably be

the total removal of the Jews."

|

By November 1923 Hitler was

convinced that the Weimar Republic was on the verge of

collapse and, together with General Ludendorff and local

nationalist groups, sought to overthrow the Bavarian government

in Munich. Bursting into a beer-hall in Munich and firing his pistol

into the ceiling, he shouted out that he was heading a new

provisional government which would carry through a revolution

against "Red Berlin." Hitler and Ludendorff then marched

through Munich at the head of 3,000 men, only to be met by

police fire which left sixteen dead and brought the attempted

putsch to an ignominious end. Hitler was arrested and tried

on 26 February 1924, succeeding in turning the tables on his

accusers with a confident, propagandist speech which ended

with the prophecy: "Pronounce us guilty a thousand times over:

the goddess of the eternal court of history will smile and tear to

pieces the State Prosecutor's submission and the court's

verdict for she acquits us." Sentenced to five years'

imprisonment in Landsberg fortress, Hitler was released after

only nine months during which he dictated Mein Kampf

(My Struggle) to his loyal follower, Rudolf Hess.

Subsequently the "bible" of the Nazi Party, this crude,

half-baked hotchpotch of primitive Social Darwinism, racial myth,

anti-Semitism and lebensraum fantasy had sold over five million

copies by 1939 and been translated into eleven languages.

The

failure of the Beer-Hall putsch and his period of

imprisonment transformed Hitler from an incompetent

adventurer into a shrewd political tactician, who henceforth

decided that he would never again confront the gun barrels of army and

police until they were under his command. He concluded that

the road to power lay not through force alone but through

legal subversion of the Weimar Constitution, the building of a

mass movement and the combination of parliamentary strength

with extra-parliamentary street terror and intimidation.

Helped by Goering and Goebbels he began to reassemble his

followers and rebuild the movement which had disintegrated in his

absence.

Rise of the Nazi Party

In

January 1925 the ban on the Nazi Party was removed and Hitler regained

permission to speak in public. Outmaneuvering the "socialist" North

German wing of the Party under Gregor Strasser, Hitler re-established

himself in 1926 as the ultimate arbiter to whom all factions appealed in

an ideologically and socially heterogeneous movement. Avoiding rigid,

programmatic definitions of National Socialism which would have

undermined the charismatic nature of his legitimacy and his claim to

absolute leadership, Hitler succeeded in extending his appeal beyond

Bavaria and attracting both Right and Left to his movement.

Though

the Nazi Party won only twelve seats in the 1928 elections, the onset

of the Great Depression with its devastating effects on the middle

classes helped Hitler to win over all those strata in German society who

felt their economic existence was threatened. In addition to peasants,

artisans, craftsmen, traders, small businessmen, ex-officers, students

and declasse intellectuals, the Nazis in 1929 began to win over the big

industrialists, nationalist conservatives and army circles. With the

backing of the press tycoon, Alfred Hugenberg, Hitler received a

tremendous nationwide exposure just as the effects of the world economic

crisis hit Germany, producing mass unemployment, social dissolution,

fear and indignation. With demagogic virtuosity, Hitler played on

national resentments, feelings of revolt and the desire for strong

leadership using all the most modern techniques of mass persuasion to

present himself as Germany's redeemer and messianic saviour.

|

In the 1930 elections the Nazi vote

jumped dramatically from 810,000 to 6,409,000 (18.3 percent

of the total vote) and they received 107 seats in the

Reichstag. Prompted by Hjalmar Schacht and Fritz Thyssen, the

great industrial magnates began to contribute liberally to

the coffers of the NSDAP, reassured by Hitler's performance

before the Industrial Club in Dusseldorf on 27 January 1932

that they had nothing to fear from the radicals in the Party. The

following month Hitler officially acquired German citizenship

and decided to run for the Presidency, receiving 13,418,011

votes in the run-off elections of 10 April 1931 as against

19,359,650 votes for the victorious von Hindenburg , but four

times the vote for the communist candidate, Ernst Thaelmann.

In the Reichstag elections of July 1932 the Nazis emerged as

the largest political party in Germany, obtaining nearly fourteen

million votes (37.3 per cent) and 230 seats. Although the NSDAP

fell back in November 1932 to eleven million votes (196

seats), Hitler was helped to power by a camarilla of

conservative politicians led by Franz von Papen, who

persuaded the reluctant von Hindenburg to nominate "the

Bohemian corporal" as Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933.

Once

in the saddle, Hitler moved with great speed to outmanoeuvre his

rivals, virtually ousting the conservatives from any real participation

in government by July 1933, abolishing the free trade unions,

eliminating the communists, Social Democrats and Jews from any role in

political life and sweeping opponents into concentration camps. The

Reichstag fire of 27 February 1933 had provided him with the perfect

pretext to begin consolidating the foundations of a totalitarian

one-party State, and special "enabling laws" were ramrodded through the

Reichstag to legalize the regime's intimidatory tactics.

With

support from the nationalists, Hitler gained a majority at the last

"democratic" elections held in Germany on 5 March 1933 and with cynical

skill he used the whole gamut of persuasion, propaganda, terror and

intimidation to secure his hold on power. The seductive notions of

"National Awakening" and a "Legal Revolution" helped paralyse potential

opposition and disguise the reality of autocratic power behind a facade

of traditional institutions.

Hitler As Fuhrer

|

The destruction of the radical SA

leadership under Ernst Rohm in the Blood Purge of June 1934

confirmed Hitler as undisputed dictator of the Third Reich

and by the beginning of August, when he united the positions

of Fuhrer and Chancellor on the death of von Hindenburg, he

had all the powers of State in his hands. Avoiding any

institutionalization of authority and status which could

challenge his own undisputed position as supreme arbiter,

Hitler allowed subordinates like Himmler, Goering and Goebbels to mark

out their own domains of arbitrary power while multiplying

and duplicating offices to a bewildering degree.

During

the next four years Hitler enjoyed a dazzling string of

domestic and international successes, outwitting rival political

leaders abroad just as he had defeated his opposition at home. In

1935 he abandoned the Versailles Treaty and began to build up

the army by conscripting five times its permitted number. He

persuaded Great Britain to allow an increase in the naval

building programme and in March 1936 he occupied the

demilitarized Rhineland without meeting opposition. He began

building up the Luftwaffe and supplied military aid to Francoist

forces in Spain, which brought about the Spanish fascist

victory in 1939.

The German rearmament

programme led to full employment and an unrestrained

expansion of production, which reinforced by his foreign

policy successes--the Rome-Berlin pact of 1936, the Anschluss

with Austria and the "liberation" of the Sudeten Germans in

1938 — brought Hitler to the zenith of his popularity. In February

1938 he dismissed sixteen senior generals and took personal

command of the armed forces, thus ensuring that he would be

able to implement his aggressive designs.

Hitler's

saber-rattling tactics bludgeoned the British and French

into the humiliating Munich agreement of 1938 and the eventual

dismantlement of the Czechoslovakian State in March 1939. The

concentration camps, the Nuremberg racial laws against the

Jews, the persecution of the churches and political

dissidents were forgotten by many Germans in the euphoria of Hitler's

territorial expansion and bloodless victories. The next

designated target for Hitler's ambitions was Poland

(her independence guaranteed by Britain and France) and, to

avoid a two-front war, the Nazi dictator signed a pact of

friendship and non-aggression with Soviet Russia.

World War II

On

September 1, 1939, German armed forces invaded Poland and

henceforth Hitler's main energies were devoted to the conduct of a war

he had unleashed to dominate Europe and secure Germany's

"living space."

The first phase of

World War II was dominated by German Blitzkrieg tactics:

sudden shock attacks against airfields, communications,

military installations, using fast mobile armor and infantry to follow

up on the first wave of bomber and fighter aircraft. Poland

was overrun in less than one month, Denmark and Norway in two

months, Holland, Belgium, Luxemburg and France in

six weeks. After the fall of France in June 1940 only Great Britain

stood firm.

|

The Battle of Britain, in which the

Royal Air Force prevented the Luftwaffe from securing aerial

control over the English Channel, was Hitler's first

setback, causing the planned invasion of the British Isles to

be postponed. Hitler turned to the Balkans and North Africa

where his Italian allies had suffered defeats, his armies rapidly

overrunning Greece, Yugoslavia, the island of

Crete and driving the British from Cyrenaica.

The

crucial decision of his career, the invasion of Soviet

Russia on June 22, 1941, was rationalized by the idea that its

destruction would prevent Great Britain from continuing the war with

any prospect of success. He was convinced that once he kicked

the door in, as he told Jodl (q.v.), "the whole rotten

edifice [of communist rule] will come tumbling down" and the

campaign would be over in six weeks. The war against Russia

was to be an anti-Bolshivek crusade, a war of annihilation in

which the fate of European Jewry would finally be sealed. At

the end of January 1939 Hitler had prophesied that "if the

international financial Jewry within and outside Europe should succeed

once more in dragging the nations into a war, the result will

be, not the Bolshevization of the world and thereby the

victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in

Europe."

As the war widened — the United

States by the end of 1941 had entered the struggle against

the Axis powers — Hitler identified the totality of Germany's

enemies with "international Jewry," who supposedly stood

behind the British-American-Soviet alliance. The policy of

forced emigration had manifestly failed to remove the Jews

from Germany's expanded lebensraum, increasing their numbers under German rule as the Wehrmacht moved East.

The

widening of the conflict into a world war by the end of

1941, the refusal of the British to accept Germany's right to

continental European hegemony (which Hitler attributed to

"Jewish" influence) and to agree to his "peace" terms, the

racial-ideological nature of the assault on Soviet Russia,

finally drove Hitler to implement the "Final Solution of

the Jewish Question" which had been under consideration since

1939. The measures already taken in those regions of Poland

annexed to the Reich against Jews (and Poles) indicated the

genocidal implications of Nazi-style "Germanization"

policies. The invasion of Soviet Russia was to set the seal on Hitler's

notion of territorial conquest in the East, which was

inextricably linked with annihilating the 'biological roots

of Bolshevism' and hence with the liquidation of all Jews

under German rule.

At first the German armies

carried all before them, overrunning vast territories, overwhelming the

Red Army, encircling Leningrad and reaching within striking distance of

Moscow. Within a few months of the invasion Hitler's armies had extended

the Third Reich from the Atlantic to the Caucasus, from the Baltic to

the Black Sea. But the Soviet Union did not collapse as expected and

Hitler, instead of concentrating his attack on Moscow, ordered a pincer

movement around Kiev to seize the Ukraine, increasingly procrastinating

and changing his mind about objectives. Underestimating the depth of

military reserves on which the Russians could call, the caliber of their

generals and the resilient, fighting spirit of the Russian people (whom

he dismissed as inferior peasants), Hitler prematurely proclaimed in

October 1941 that the Soviet Union had been "struck down and would never

rise again." In reality he had overlooked the pitiless Russian winter

to which his own troops were now condemned and which forced the

Wehrmacht to abandon the highly mobile warfare which had previously

brought such spectacular successes.

The

disaster before Moscow in December 1941 led him to dismiss

his Commander-in-Chief von Brauchitsch, and many other key

commanders who sought permission for tactical withdrawals,

including Guderian, Bock, Hoepner, von Rundstedt and Leeb,

found themselves cashiered. Hitler now assumed personal control

of all military operations, refusing to listen to advice,

disregarding unpalatable facts and rejecting everything that

did not fit into his preconceived picture of reality. His

neglect of the Mediterranean theatre and the Middle East, the

failure of the Italians, the entry of the United States into

the war, and above all the stubborn determination of the

Russians, pushed Hitler on to the defensive. From the winter of 1941

the writing was on the wall but Hitler refused to countenance

military defeat, believing that implacable will and the rigid

refusal to abandon positions could make up for inferior

resources and the lack of a sound overall strategy.

Convinced

that his own General Staff was weak and indecisive, if not openly

treacherous, Hitler became more prone to outbursts of blind, hysterical

fury towards his generals, when he did not retreat into bouts of

misanthropic brooding. His health, too, deteriorated under the impact of

the drugs prescribed by his quack physician, Dr. Theodor Morell.

Hitler's personal decline, symbolized by his increasingly rare public

appearances and his self-enforced isolation in the "Wolf's Lair," his

headquarters buried deep in the East Prussian forests, coincided with

the visible signs of the coming German defeat which became apparent in

mid-1942.

Allied Victory and Hitler's Death

Rommel's

defeat at El Alamein and the subsequent loss of North Africa

to the Anglo-American forces were overshadowed by the

disaster at Stalingrad where General von Paulus's Sixth Army

was cut off and surrendered to the Russians in January 1943.

In July 1943 the Allies captured Sicily and Mussolini's

regime collapsed in Italy. In September the Italians signed

an armistice and the Allies landed at Salerno, reaching Naples

on 1 October and taking Rome on June 4, 1944. The Allied invasion of

Normandy followed on June 6, 1944 and soon a million Allied

troops were driving the German armies eastwards, while from

the opposite direction the Soviet forces advanced

relentlessly on the Reich. The total mobilization of the

German war economy under Albert Speer and the energetic

propaganda efforts of Joseph Goebbels to rouse the fighting

spirit of the German people were impotent to change the fact

that the Third Reich lacked the resources equal to a struggle

against the world alliance which Hitler himself had provoked.

|

Allied bombing began to have a

telling effect on German industrial production and to undermine the

morale of the population. The generals, frustrated by Hitler's total

refusal to trust them in the field and recognizing the inevitability of

defeat, planned, together with the small anti-Nazi Resistance inside the

Reich, to assassinate the Fuhrer on 20 July 1944, hoping to pave the

way for a negotiated peace with the Allies that would save Germany from

destruction. The plot failed and Hitler took implacable vengeance on the

conspirators, watching with satisfaction a film of the grisly

executions carried out on his orders.

As

disaster came closer, Hitler buried himself in the unreal world of the

Fuhrerbunker in Berlin, clutching at fantastic hopes that his "secret

weapons," the V-1 and V-2 rockets, would yet turn the tide of war. He

gestured wildly over maps, planned and directed attacks with

non-existent armies and indulged in endless, night-long monologues which

reflected his growing senility, misanthropy and contempt for the

"cowardly failure" of the German people.

As

the Red Army approached Berlin and the Anglo-Americans reached

the Elbe, on 19 March 1945 Hitler ordered the destruction of what

remained of German industry, communications and transport

systems. He was resolved that, if he did not survive, Germany

too should be destroyed. The same ruthless nihilism and

passion for destruction which had led to the extermination of

six million Jews in death camps, to the biological

"cleansing" of the sub-human Slavs and other subject peoples

in the New Order, was finally turned on his own people.

On

April 29, 1945, he married his mistress Eva Braun and dictated his

final political testament, concluding with the same

monotonous, obsessive fixation that had guided his career

from the beginning: "Above all I charge the leaders of the

nation and those under them to scrupulous observance of the

laws of race and to merciless opposition to the universal

poisoner of all peoples, international Jewry."

The

following day Hitler committed suicide, shooting himself through the

mouth with a pistol. His body was carried into the garden of the Reich

Chancellery by aides, covered with petrol and burned along with that of

Eva Braun. This final, macabre act of self-destruction appropriately

symbolized the career of a political leader whose main legacy to Europe

was the ruin of its civilization and the senseless sacrifice of human

life for the sake of power and his own commitment to the bestial

nonsense of National Socialist race mythology. With his death nothing

was left of the "Greater Germanic Reich," of the tyrannical power

structure and ideological system which had devastated Europe during the

twelve years of his totalitarian rule.

Post a Comment